Me and my partner climbed Mithral Dihedral, a 5.9+ or 5.10a 1000 feet long alpine route on Mt. Russell in the High Sierras, California. Mt. Russell has an elevation of 14,094 feet (4,296 m) and is the seventh-highest peak in the state. Although a majestic peak, Mt. Russell is often overlooked by the Whitney zone visitors in favor of the much popular Mt. Whitney.

Mt. Whitney is more popular for two reasons; for it being the highest peak in the contiguous United States, and the fact that it offers a couple of classic moderates along with the much popular and accessible Mountaineer’s going at Class III scramble route for those who want something more than the long and winding 22 miles round trip of the Whitney trail.

Having said that, both the classic rock climbs on Mt. Whitney, the East Face (5.7) and the East Buttress (5.7) both offer amazing climb on the Sierra granite and are long and serious and should not be underestimated. Both these climbs are accessible from the Iceberg lake camp with an approach of mere 30 minutes. Plus, the Iceberg lake camp is one of the most rugged and beautiful setting I have ever camped in the United States so far.

Perched well over 12600 feet, Iceberg lake sits pretty at the base of awe-inspiring East Face of Whitney and the adjacent Needles. These mountains looms large overhead and present an awe-inspiring facade as you look out of your tent. However, some things are just larger than our objectives, including the mighty mountains themselves. As in this image, the milky way dwarfs and overpowers Mt. Whitney as well as anything else that stands tall.

I was certainly not ready for the Harding Route on Keeler Needle – a very sustained 5.10c route in the high alpine realms and with 2000 feet of climbing on steep granite it is one of the Peter Croft’s big four in the High Sierras . However, I wanted to test myself on something more than what East face or East buttress of Mt. Whitney had to offer, and the nearby Mt. Russell just beyond the col offered a couple of viable routes to check where my boundaries lay. Although, I wanted to do these classics on Whitney, the time on hand and the physical capacities precluded any chance of doing it all in this trip. Hence, I focused my attention solely on Mt. Russell.

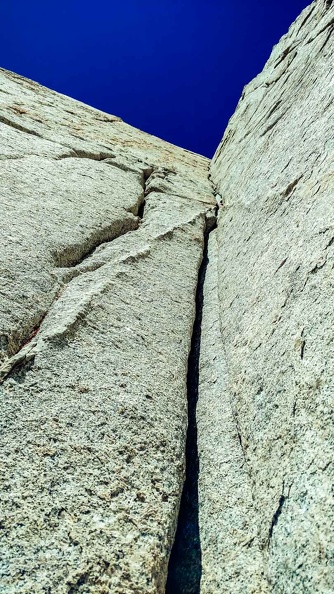

Mt.Russell offers two classic lines – the Fishhook arete at 5.9 and the Mithril dihedral at 5.9+/.10a. Now, on paper these grades may appear quite close to each other, but be rest assured that Mithril is a more than just a letter grade up in every aspect – sustained, steeper, serious exposure and involves a challenging offwidth all at nearly 14,000 feet. Fishhook arete is wonderful in its own right, but Mithril is definitely a notch up. However, I was to discover this difference between the two climbs only after I climbed it.

In the hindsight, climbing Mithril Dihedral was not a great idea, especially since the hardest trad lead I had ever done before that climb was one pitch of 5.10a at Tennessee wall – a 75 odd feet of finger crack at almost sea level.This is besides the fact that I am Florida based gym climber with a flair for face climbing on southern sandstone and almost no access, skills or affinity for crack climbs, at altitudes and on granite! Add to the fact that my partner in crime was no better than me. Mithril in comparison offers 1000+ feet of crack climbing (including an offwidth section) at around 14000 feet and sustained pitches at 5.10 on sheer and cold granite of the sierras. See the mismatch here?

No wonder it was an ordeal for us. We know that we almost epic’ed it with a bivy at 13,500 feet on a tiny and exposed 4×4 feet ledge and almost froze ourselves through the night. We turned probably a 8 hour climb into a two day affair. We know things could have gone wrong. But, they did not. We successfully survived and completed the climb, taking much longer than what any competent party will take and making a hell lot of more errors that cost us time and energy.

Most of the people (probably those who have not gauged the seriousness of the climb) applauded and congratulated us. A few others, who probably are more accomplished than us on alpine rock, especially crack climbing, suggested that we should hone our skills further before pushing our limits on the big alpine climbs. While it feels good to be applauded, the critical feedback is priceless.

While I appreciate the critical concerns, I do have a different perspective on this. The very reason I climb – be it in the gym, on boulders, clipping bolts, plugging gear or chopping ice – the sense of adventure arises from the fact that I do not know what’s in store. Will I be able to maintain that body tension to make the next move in that bouldering cave? Or will I be able to find a decent protection while I am desperately fumbling with my rack high above my last piece? In either case this element of unpredictability is what drives me to indulge in climbing. While the consequences of these unpredictable occurrences may have drastically different outcomes in bouldering vis-a-vis alpine climbing, the fact that both allows me a chance to venture into the unknown and explore my limits is what defines the essence of climbing for me.

I am not advocating that one must reach out far and beyond one capabilities. Neither am I saying that one must go unprepared/untrained and challenge themselves to test their limits. I am saying that one can never find (and expand) their limits if one decides to play safe within their limits. And make no mistake, there is nothing wrong in playing within your limits. But to find your true limits, you need to go beyond it.

I feel attempting Harding’s route on Keeler Needle would have been foolish. East Buttress on Mt. Whitney would have been playing safe. Mithril Dihedral was definitely pushing it, but not unrealistic. We made mistakes and wished plenty of times while on the route that we stick to sport climbing. We vowed not to venture into technical alpine climbs and to push our limits on hard sport climbs. We messed up pretty bad in terms of rope management and I wandered off the route on a couple of occasions.

Yet when we made our entry on the summit register, we were happy, content and smiling. We definitely need to train more and climb more granite and spend more time climbing cracks. However, there are constraints that precludes these possibilities. Will these constraints go? We don’t know. What we know if that we cannot let these constraints define what we can do and what we cannot. The only way to know the answers is to get out there and try it.

So, do I label my climb as a success? Failure? Well, honestly, I am not sure. I would have loved to do it in one day. Heck, I would have loved to do both the routes on Mt. Russell in one day. And I’ll surely be back to attempt it, along with Keeler needle someday. But for today, my notes look like this –

- Whitney hike in (RR with 76lbs and PK with 42lbs) for 6000+ feet elevation gain in 2 days. Energy sapping with heavy loads – longer recovery time before the actual climb. No time for acclimatization, fatigue from approach and poor efficiency caused Mt. Russell climb of Mithral Dihedral (5.9+/.10a). Took 2-days what should have been a 10 hour day.

Lessons learnt

- Acclimatize well before any big climb

- Get used to crack and build better mountain fitness to move faster in the mountains

- Travel lighter, buy lighter gear (rope and tent), go with 50/60mm skinny on alpine routes as against the 10mm 70m we carries on this one. (I did not want to buy skinny 50m for one of alpine climb that I do once in a couple of years – was a mistake on this one)

- Do more of within reach big climbs in 5.8/5.9 grades

- Do better rope management

- Do speedier belay transitions

- Move closer to the mountains

- Go light and fast on approach – saves energy

- Keep photography trips and climbing trips separate – carrying the heavy camera, lens and tripod was a mistake and detrimental to our climbing performance. But the timelapse video we managed to make really make me rethink this point.

- Get out a lot more so that you know what you don’t know.

After this trip, I know for sure that as an aspiring alpine climber I have shit alpine craft. But then what do I expect climbing plastic in a Florida gym? More important is the fact that I learnt it and I know that I don’t know.